ACOMAT member flying a drone for monitoring their forestry concession. Source: ACCA.

The southern Peruvian Amazon (Madre de Dios region), is threatened by illegal mining, logging, and illegal deforestation.

In response, an association of forest concessionaires (known as ACOMAT) is implementing a comprehensive monitoring system that links the use of technology (satellites and drones) with legal action.

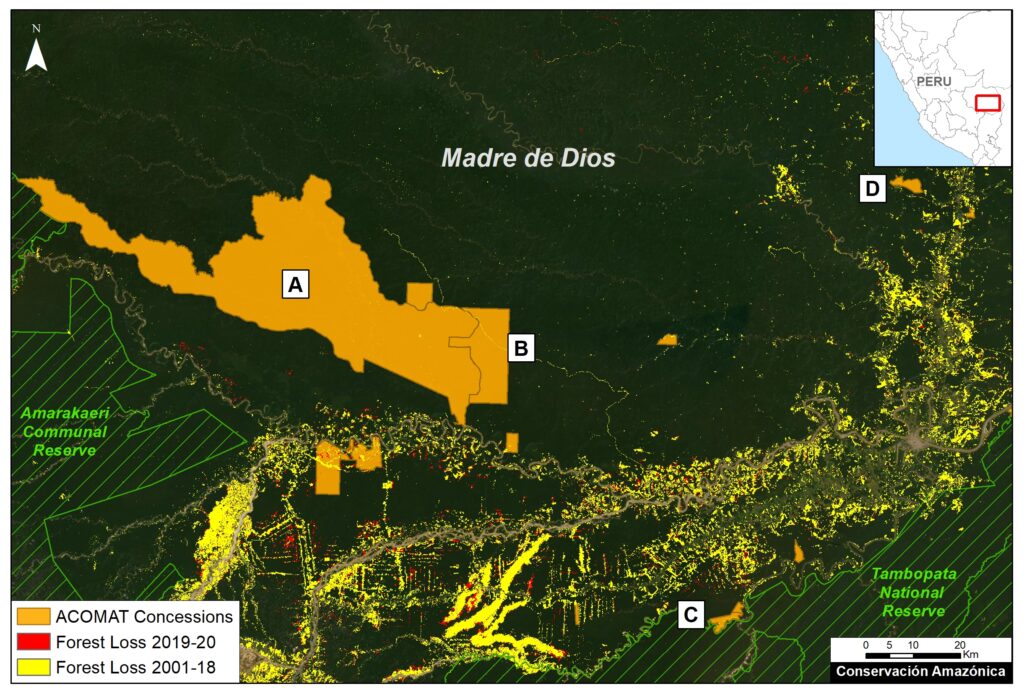

ACOMAT was formed in 2012 and now comprises 15 forestry concessions, covering 440,000 acres (178,000 hectares) in the southern Peruvian Amazon (see Base Map). Most of the concessions are alternatives to logging, such as Brazil nuts, Conservation, and Ecotourism.

This comprehensive system has three main elements:

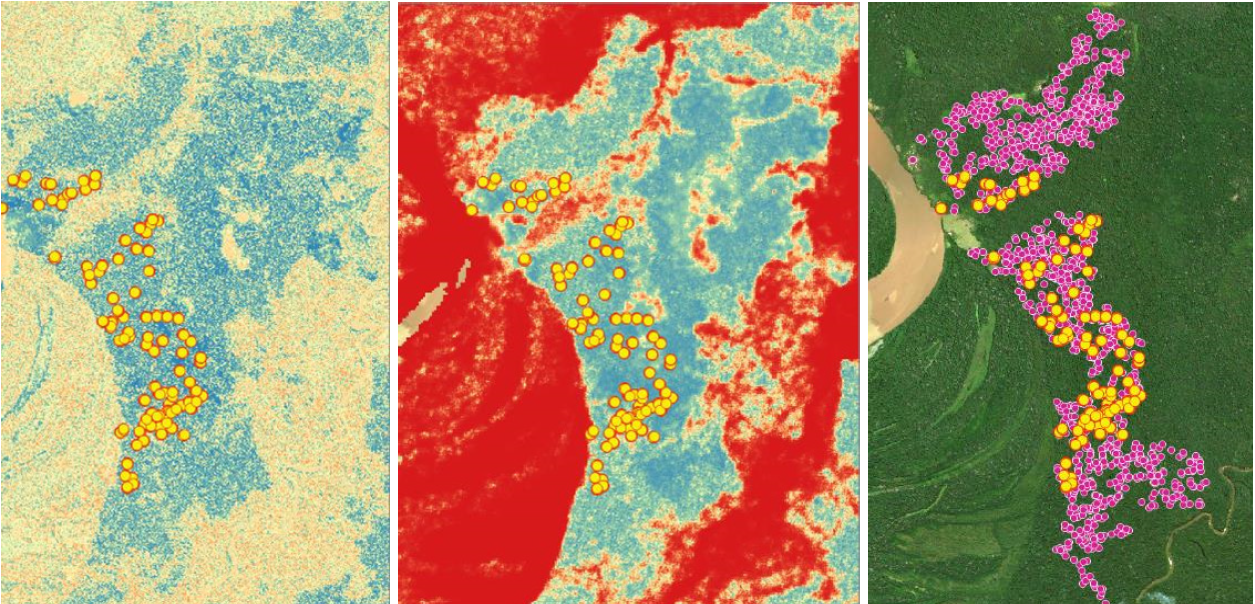

- Real-time, satellite-based forest loss monitoring (such as GLAD alerts) to quickly detect any possible new threats, even across vast and remote areas.

- Field patrols with drone flights to verify forest alerts (or monitor threatened areas) with very high resolution images.

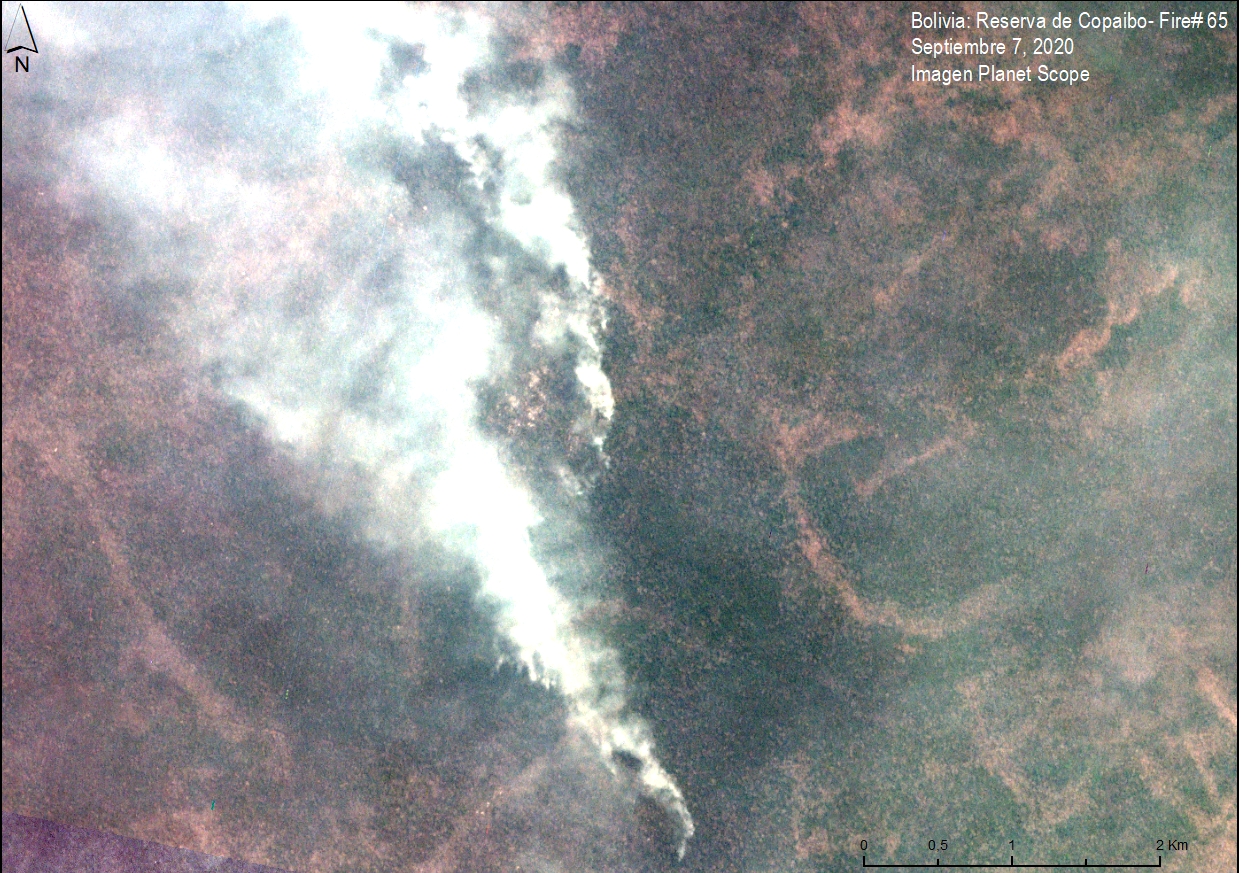

- If suspected illegality is documented, initiate a criminal or administrative complaint, utilizing both the satellite and drone-based evidence.

In the case of ACOMAT, during 2019 they conducted 26 drone patrols and filed 15 legal complaints with the regional Environmental Prosecutor’s Office, known as FEMA. Below, we describe several of these cases.

Note that there is high potential to replicate this comprehensive monitoring model at the level of forest custodians (for example, concessionaires and indigenous communities) in the Amazon and other tropical forests.

Key ACOMAT Cases

Next, we describe four cases where comprehensive monitoring was performed (see Insets A-D on the Base Map).

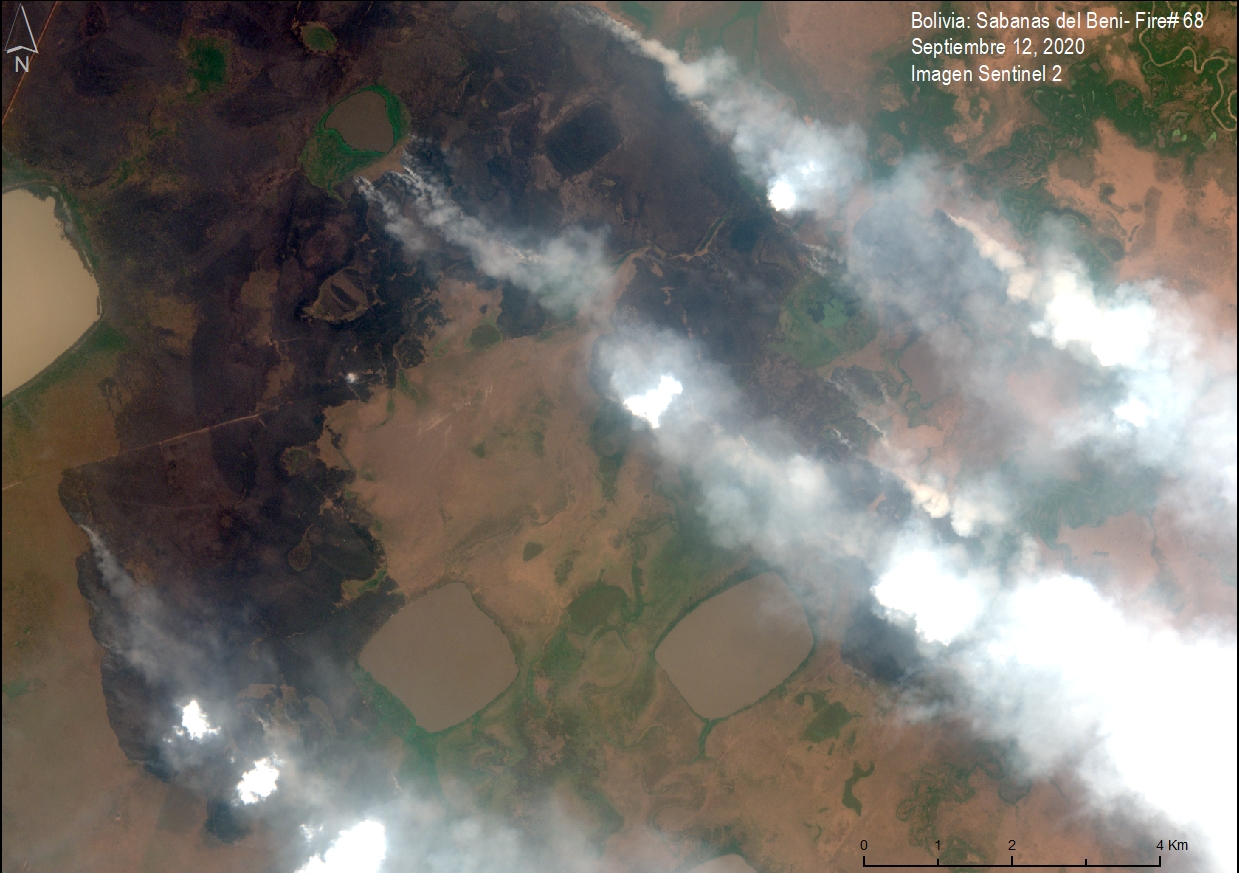

Base Map. ACOMAT concessions. Data: ACCA, MINAM/PNCBMCC, SERNANP.

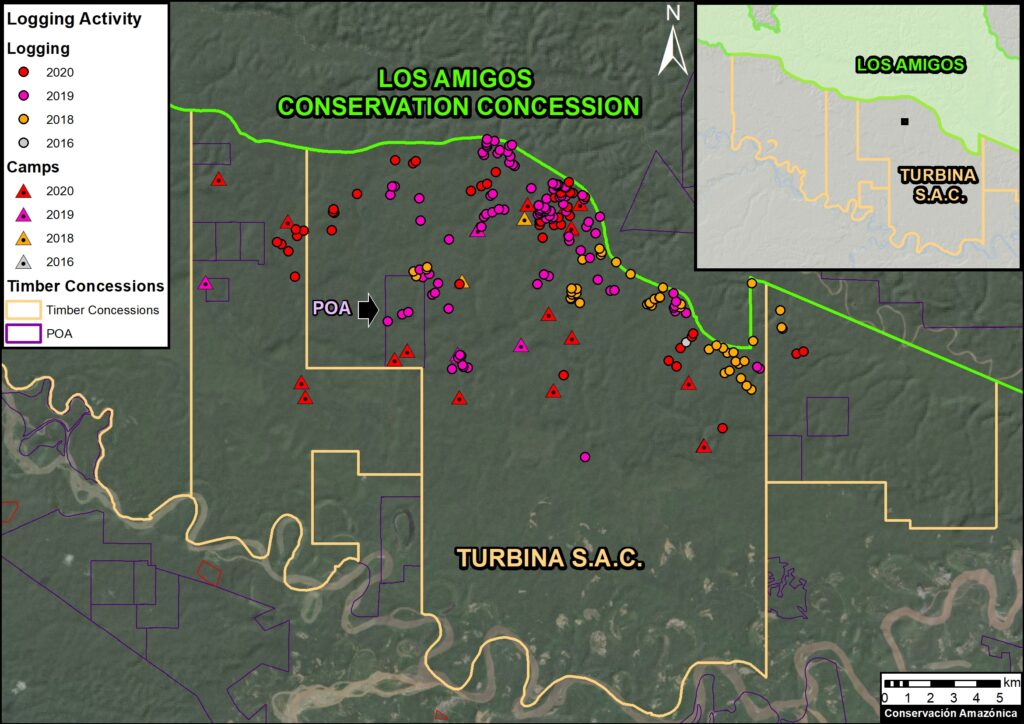

A. Illegal logging in the Los Amigos Conservation Concession

In October 2019, a patrol was carried out to investigate a threatened area within the Los Amigos Conservation Concession (the world’s first Conservation Consession). During the patrol, which included five drone flights, illegal logging was documented, including stumps with sawn trees , paths for the transfer of wood to a nearby river, and abandoned camps. The drone images were added as evidence in support of the previously filed criminal complaint to the FEMA in Madre de Dios. Below we present two striking images from the drone flights, clearly showing the illegal logging. Status of the Complaint: In Preliminary Investigation.

Case A. Illegal logging in the Los Amigos Conservation Concession, identified with drone overflight. Source: ACCA.

Case A. Illegal logging in the Los Amigos Conservation Concession, identified with drone overflight. Source: ACCA.

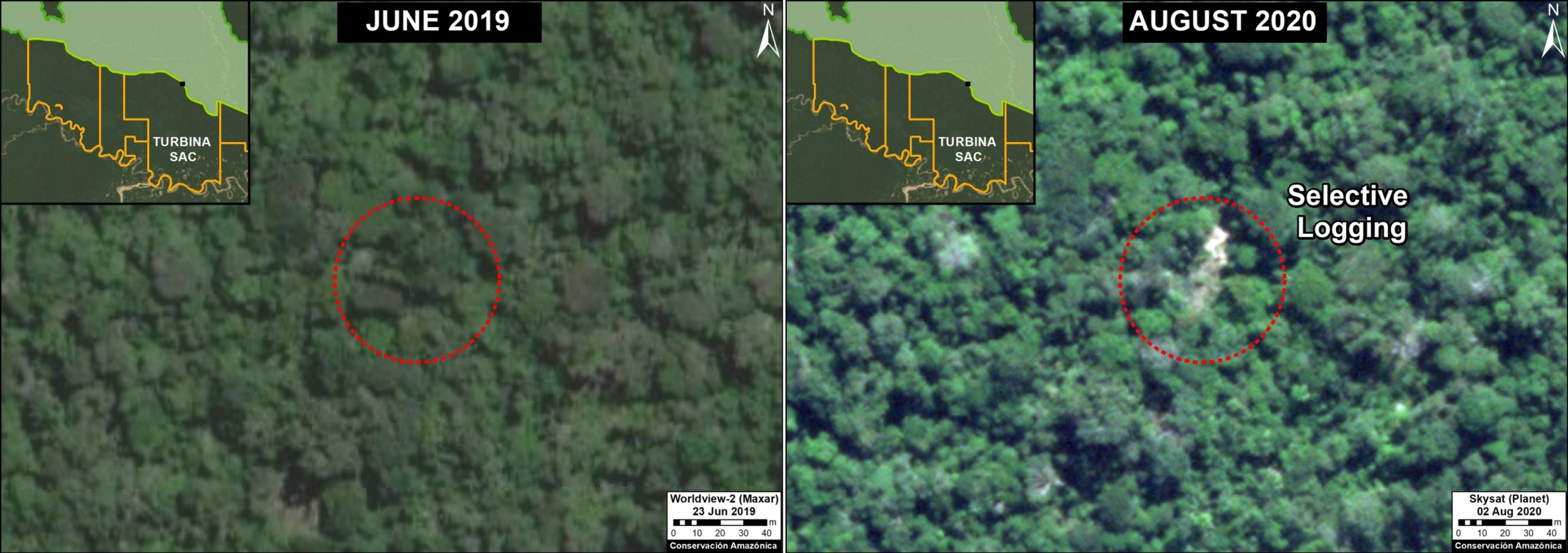

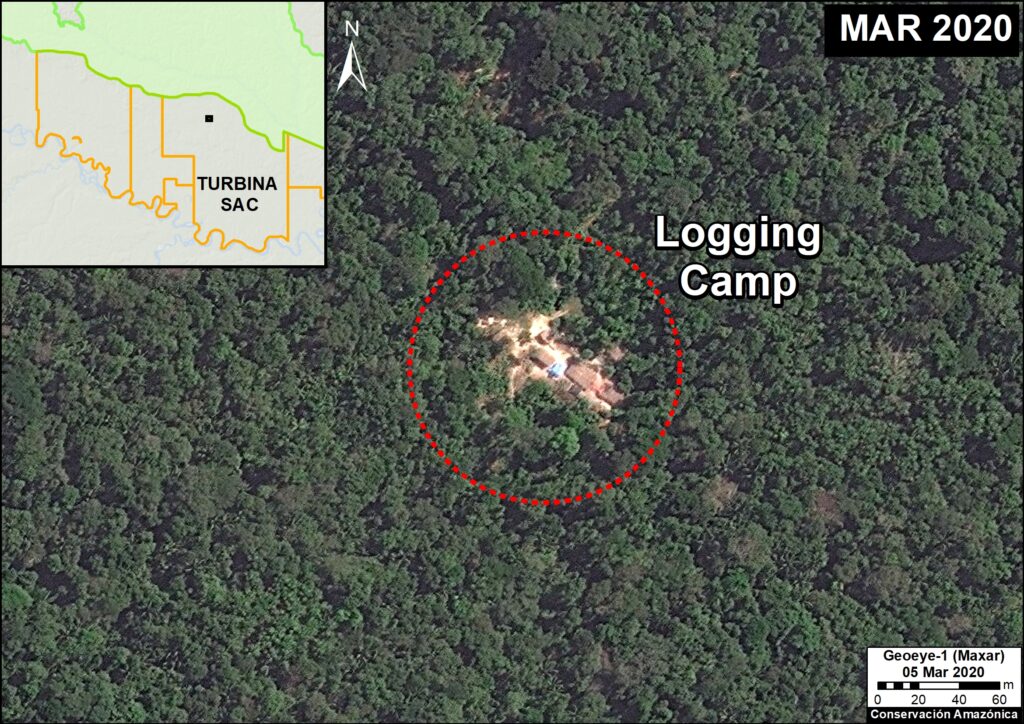

B. Ilegal Logging in the MADEFOL Forestry Concession

In May 2019, a field patrol was carried out to investigate a threatened area within the MADEFOL forestry concession. During the patrol, which included two drone flights, illegal logging was documented, including stumps with sawn trees, a recently abandoned camp, and an access road. With the drone images as evidence, a new criminal complaint was filed with the FEMA in Madre de Dios. Below is an image from the drone flights, clearly showing the evidence of illegal logging. Status of the complaint: In qualification.

Case B. Illegal logging in the “MADEFOL” forestry concession identified with drone overflight. Source: ACCA.

C. Illegal Gold Mining in a Conservation Concession

In May 2019, a field patrol was carried out in the “Inversiones Manu SAC” Conservation Concession to investigate an area that had previously been affected by illegal gold miners. During the patrol, which included two drone flights, illegal gold mining was documented in the Malinowski River. With the drone images as evidence, a new criminal complaint was filed with the FEMA in Madre de Dios. Below is a drone image clearly showing the evidence of illegal gold mining. Status of the complaint: Preliminary Investigation.

Case C. Illegal mining in the Conservation Concession “Inversiones Manu SAC,” identified with a drone overflight. Source: ACCA.

D. Deforestation in a Brazil Nut Concession

In October 2019, a patrol was carried out to investigate an early warning deforestation alert within the “Sara Hurtado Orozco B” Brazil nut concession.

During the patrol, which included one drone flight, the recent deforestation of five acres (two hectares) was documented. With the drone images, a new criminal complaint was filed with the FEMA of Madre de Dios. It should be noted that this concession was being investigated for a separate illegal deforestation event. Below is one of the images of the drone flight, clearly showing the illegal deforestation. Status of the complaint: In preliminary proceedings.

Case D. Deforestation in the “Sara Hurtado Orozco B” Brazil Nut Forest Concession. Source: ACCA.

Importance of the “ACOMAT Model”

We have started using the term “Acomat model” to refer to the innovative use of the three elements described above (real-time monitoring, drone flights, and criminal complaints) by the ACOMAT concessionaires.

ACOMAT was created in 2012, and since 2017 has received crucial support from the organization Conservation Amazónica-ACCA, supported by funds from Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative (NICFI), led by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD).

This project has provided training on all three major aspects, satellite-based monitoring alerts, drones, and the legal process. Concessionaires now receive deforestation alerts to their phones, have the ability to organize and conduct field patrols, and some are trained to perform their own drone flights.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Segura (DAI), M.E. Gutierrez (ACCA), D. Suarez (ACCA), H. Balbuena (ACCA), M. Silman (WFU), and G. Palacios for their helpful comments on this report.

This report was conducted with technical assistance from USAID, via the Prevent project. Prevent is an initiative that, over the next 5 years, will work with the Government of Peru, civil society, and the private sector to prevent and combat environmental crimes in Loreto, Ucayali and Madre de Dios, in order to conserve the Peruvian Amazon.

This report was conducted with technical assistance from USAID, via the Prevent project. Prevent is an initiative that, over the next 5 years, will work with the Government of Peru, civil society, and the private sector to prevent and combat environmental crimes in Loreto, Ucayali and Madre de Dios, in order to conserve the Peruvian Amazon.

This publication is made possible with the support of the American people through USAID. Its content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US government.

This work was also supported by NORAD (Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation) and ICFC (International Conservation Fund of Canada).

Citation

Finer M, Castañeda C, Novoa S, Paz L (2020) Drones and Legal Action in the Peruvian Amazon. MAAP 126.

received all the technology she needed to do regular surveillance of her forest remotely, including a Mavic 2 drone, an iPhone 7 plus to run satellite monitoring smartphone apps, a computer and a printer.

received all the technology she needed to do regular surveillance of her forest remotely, including a Mavic 2 drone, an iPhone 7 plus to run satellite monitoring smartphone apps, a computer and a printer.

This report was conducted with technical assistance from USAID, via the Prevent project. Prevent is an initiative that, over the next 5 years, will work with the Government of Peru, civil society, and the private sector to prevent and combat environmental crimes in Loreto, Ucayali and Madre de Dios, in order to conserve the Peruvian Amazon.

This report was conducted with technical assistance from USAID, via the Prevent project. Prevent is an initiative that, over the next 5 years, will work with the Government of Peru, civil society, and the private sector to prevent and combat environmental crimes in Loreto, Ucayali and Madre de Dios, in order to conserve the Peruvian Amazon.

are cared for by local staff at the station, hatching between 65-80 days after being laid. Once the eggs have hatched, the baby turtles are kept in conditioned water ponds to monitor their growth until they are large enough to be released into their natural habitat. Of this batch, 85% of the eggs were hatched.

are cared for by local staff at the station, hatching between 65-80 days after being laid. Once the eggs have hatched, the baby turtles are kept in conditioned water ponds to monitor their growth until they are large enough to be released into their natural habitat. Of this batch, 85% of the eggs were hatched.

Loading...

Loading...