For the past year, we had been working on legal and technical requirements needed to create the 78,000-acre Porvenir Protected Area in the Pando region of Bolivia, and on creating the necessary framework to support its long-term management and protection. This work paid off; even with the challenges of the pandemic, the municipal government has officially declared Porvenir a protected area in early October. Additionally, another protected area nearby, Puerto Rico, is in the final stages of being declared and we expect the process to be completed by the end of the year. Together, these two new conservation areas will protect almost 400,000 acres of forests – a major win for the Bolivian Amazon!

For the past year, we had been working on legal and technical requirements needed to create the 78,000-acre Porvenir Protected Area in the Pando region of Bolivia, and on creating the necessary framework to support its long-term management and protection. This work paid off; even with the challenges of the pandemic, the municipal government has officially declared Porvenir a protected area in early October. Additionally, another protected area nearby, Puerto Rico, is in the final stages of being declared and we expect the process to be completed by the end of the year. Together, these two new conservation areas will protect almost 400,000 acres of forests – a major win for the Bolivian Amazon!

In both of these areas, the process for their creation and management requires an important baseline of information on the biodiversity that lives there and on the ecosystem services that they provide (that is, a quantification of the many benefits to humans get from these forest ecosystems). This way, the management of the natural resources of the area will be sustainable and will keep these centuries-old forests healthy and productive. We provided the communities and the local government with this key ecological information, including physical ecosystem information, inventories of flora and fauna, climate analysis, and the identification of threatened species and of species with the potential for sustainable use that could raise families’ income.

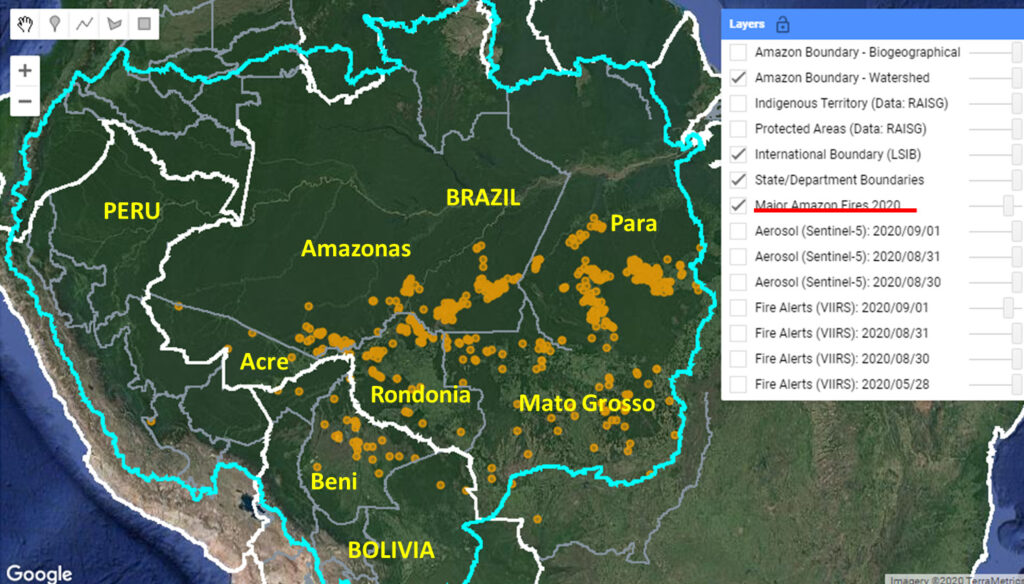

Given the heavy amount of fieldwork needed to create a conservation area, it has been a challenge working within a global pandemic and quarantine restrictions in Bolivia, as it has kept our experts from making the necessary field expeditions to carry out this work. However, we adapted our scientific methodology to continue to move forward given these extraordinary conditions. We developed a survey of all of the studies, literature, and data collections made over the past years and we used geomatic tools (that is, geographic information systems (GIS), remote sensing using satellites, and high-tech drones) to gather data on the groups of flora and fauna in both areas. With this adaptation, we were able to gather sufficient information to support the government in the formal declaration process for Porvenir to become a protected area, and in moving forward to do the same for the Puerto Rico area.

Given the heavy amount of fieldwork needed to create a conservation area, it has been a challenge working within a global pandemic and quarantine restrictions in Bolivia, as it has kept our experts from making the necessary field expeditions to carry out this work. However, we adapted our scientific methodology to continue to move forward given these extraordinary conditions. We developed a survey of all of the studies, literature, and data collections made over the past years and we used geomatic tools (that is, geographic information systems (GIS), remote sensing using satellites, and high-tech drones) to gather data on the groups of flora and fauna in both areas. With this adaptation, we were able to gather sufficient information to support the government in the formal declaration process for Porvenir to become a protected area, and in moving forward to do the same for the Puerto Rico area.

Special thanks to Andes Amazon Fund (AAF), the Sheldon and Audrey Katz Foundation, and all individuals and organizations whose generous support made this project possible.

Our novel

Our novel

Loading...

Loading...