As leaders in conservation in the Amazon for the past 20+ years, we often receive questions from schools and students eager to learn more about the Amazon Rainforest and our conservation efforts. In this blog post, we provide some key information that we hope will be useful for your research and school projects.

Unfortunately, due to limited time and capacity, our very small team based in Washington, DC cannot participate in interviews for school projects at this time. However, we hope this FAQ document and the resources listed below will help students gain a better understanding of the Amazon Rainforest and our efforts to protect it.

ABOUT THE AMAZON RAINFOREST

Why is the Amazon Rainforest important?

The Amazon is home to more than 10% of the world’s known wildlife species, with more than 100 new species discovered each year. It is an incredibly diverse ecosystem consisting of forests, rivers, and savannas that all work together to help regulate the planet’s climate by absorbing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and sequestering it into the ground. Additionally, the Amazon is not only home to a diverse range of fauna and flora, but also to local Indigenous communities and over 400 tribes, each with a distinct culture, language, and territory. These people rely on resources from their forests for their daily needs, such as food, water, fiber, and traditional medicine. Protecting a healthy forest ecosystem in the Amazon helps conserve biodiversity and resources important for the survival of local people and the whole planet.

You can learn more about why the Amazon is important here.

How big is the Amazon?

The Amazon basin covers more than 1.6 billion acres across nine countries (Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, French Guiana, Guyana, Suriname). It contains the single largest tropical rainforest on the planet and covers about 40% of the South American continent. These forests stretch from the eastern foothills of the Andes Mountains to the upland glaciers, streams, and wetlands that feed the Amazon rivers which end up in the Atlantic Ocean.

Why is the Amazon being deforested and what are the main drivers of deforestation?

The main drivers of deforestation vary by region and country, so there is no single reason why the Amazon is being deforested. In reality, it’s a complex combination of reasons. Forests are sometimes cut down and cleared for the expansion of farms and agriculture, the conversion of land to cattle pasture, and illegal economic activities like logging and mining. The Amazon is also damaged by fires (in the form of forest fires as well as human-started fires for slash-and-burn agriculture or cattle ranching that may spread out of control), poorly-planned infrastructure (such as roads, which increase access deep into the forest and dams that often cause flooding and alter river structure and paths over time), and climate change (which often causes more extreme weather events like droughts and floods).

You can learn more about threats to the Amazon here.

How does deforestation impact wildlife/fauna and flora?

How does deforestation impact wildlife/fauna and flora?

Deforestation affects habitats and can limit important resources for native flora and fauna, which can cause declining populations or even contribute to the extinction of a species. Each plant and animal plays a vital role in the rainforest ecosystem. If one species is affected, it creates a chain reaction that affects others. For example, keystone species such as the Andean bear (also called the spectacled bear) are vital for seed dispersal. The Andean bear eats fruits and plants, and the seeds of those fruits and plants are generally returned to the soil through the bears’ feces. Because these bears travel far across their large home ranges, they are able to “plant” seeds of various species across long distances, helping regenerate the forest and keep ecosystems diverse as the seeds grow into new plants and trees. When the forest is deforested, the bears’ habitat gets smaller and food sources become more limited, which affects the diversity of plants they eat and their ability to disperse seeds across larger areas. These limitations lead to less plant growth, less plant diversity, and a less healthy forest ecosystem overall. Having a smaller habitat can also limit their ability to find sufficient food sources or meet a mate to reproduce. With forest habitats continuing to be threatened by deforestation and climate change, the Andean bear is considered a species vulnerable to extinction.

What is biodiversity and why is it important for the Amazon?

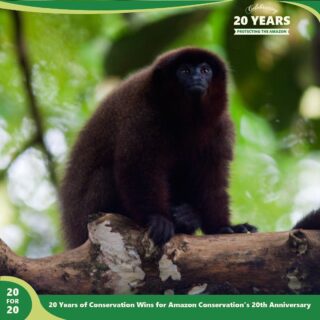

Short for “biological diversity,” “biodiversity” is a term that refers to the diverse array of wild plants and animals within an ecosystem. The Amazon is home to a wide variety of species (for example, it’s home to more than 7,500 species of butterflies!), each playing an important and unique role necessary for the ecosystem to thrive. The Amazon is considered by many scientists to be the most biodiverse place on the planet as it contains more species of plants and animals than any other terrestrial ecosystem. When one component of an ecosystem is thrown off, the entire ecosystem can become imbalanced, so protecting biological diversity is extremely important. Some ways to promote and protect biological diversity in the Amazon include pollination, seed dispersal, population and pest control, nutrient cycling, and more.

Read more about biodiversity and its importance here.

How many species are there in the Amazon? What are some of the most endangered species in the Amazon?

How many species are there in the Amazon? What are some of the most endangered species in the Amazon?

The Amazon Rainforest is the most biodiverse place on the planet. It is home to more than 3 million species of animals and plants, including 400 mammal species, 1,300 bird species, 350 reptile species, and 400 amphibian species, and each year, 100+ new species are discovered. Many of these species are endemic, meaning they are only found in the Amazon. It is also home to over 2,700 threatened or endangered species that are important to the overall health of our planet. Some notable endangered species in the Amazon are the jaguar, spectacled bear, giant armadillo, tapir, giant anteater, and the harpy eagle.

Read more about species in the Amazon here.

How does climate change impact the Amazon, its people, fauna, and flora?

How does climate change impact the Amazon, its people, fauna, and flora?

The Amazon is home to the greatest diversity of wildlife on the planet and is the birthplace of the waters that feed the Amazon River basin. Additionally, dozens of Indigenous groups, including several uncontacted tribes, reside in the region and depend on its forests and waters to continue their largely traditional lifestyle. As climate change affects global weather patterns, warmer and dryer periods will bring new stresses such as droughts, and make yearly fire seasons even more devastating, limiting critical water and forest resources that people and wildlife depend on.

Why should people care about the Amazon? How is it connected to our daily lives for those of us who live far away from it?

The Amazon’s role as a climate regulator is critical as the planet gets hotter and drier. Amazon forests store over 150 billion metric tons of carbon—more than a third of all the carbon stored in tropical forests worldwide—and they absorb 2 billion tons of CO2 each year, representing five percent of global annual emissions. This helps limit the amount of greenhouse gases present in the atmosphere, leading to less heat being trapped in the air, and keeping temperatures stable.

The world’s ecosystems are also interconnected and interdependent, and declining ecosystem health in one region can impact ecosystems and species near and far. For example, many migratory bird species go to the Amazon during colder months in the northern hemisphere. If they don’t find the food sources and habitat in the Amazon before they need to make the journey back north in the warmer months, these populations will decline and alter ecosystems in North America.

What are some resources to learn more about the Amazon Rainforest?

Other fellow conservation organizations have created wonderful resources specifically for teachers and students, such as this one and this one.

ABOUT AMAZON CONSERVATION ASSOCIATION

What is Amazon Conservation doing to protect the Amazon Rainforest?

What is Amazon Conservation doing to protect the Amazon Rainforest?

We’re the type of non-profit organization that does a little bit of everything — whatever it takes to protect the forest! Conservation to us is not a one-size-fits-all solution. As the Amazon Rainforest is so vast and diverse, it requires a big-picture approach that adapts to the needs of each region and its people.

Our comprehensive approach to conservation is developed from three key areas of work: protecting wild places, empowering people, and putting science and technology to work. Together, these areas allow us to create conservation solutions to benefit both nature and people. Some examples of the work we do include reforestation, creating new protected areas, sustainably managing existing protected areas, helping local people build sustainable economies from natural resources from the forest, using technology to stop illegal deforestation, creating spaces for scientists and students to do research in the Amazon, and so much more.

How we work in the Amazon is also important and unique. We are an alliance of three local sister organizations (Amazon Conservation in the US, Conservación Amazónica-ACCA in Peru, and Conservación Amazónica-ACEAA in Bolivia). We have the shared goal of protecting the Amazon and working together to increase each organization’s impact. We also have an impact in other Amazonian countries like Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela, and Suriname by working with local partners to detect and stop deforestation as it’s happening through our Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Program (MAAP). To implement our on-the-ground efforts, we collaborate a lot with local communities, governments, Indigenous groups, scientists, and other non-governmental organizations.

Read more about our conservation approach and strategy here.

Where does Amazon Conservation work?

We work on the ground across five interconnected landscapes in Peru and Bolivia: the Manu-Madidi Biodiversity Corridor, Uncontacted Indigenous Peoples Homeland, Productive Forests, Andean Living Waters, and Amazon savannas. Each of these unique landscapes is home to diverse ecosystems, each with its own threats and opportunities, which provide the basis for our unique conservation solutions. Our bold new strategy increases our impact by ensuring the long-term conservation of these 124 million acres of forests, savannas, wetlands, glaciers, and other irreplaceable habitats in these regions. In addition to our work on the ground, our real-time monitoring covers the entirety of the Amazon basin, providing local people, decision-makers, the media, and the general public with key analysis of what is happening across the region to help drive action locally and at scale.

Read more about these landscapes here.

What is the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Program (MAAP) and how does it help combat deforestation?

What is the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Program (MAAP) and how does it help combat deforestation?

Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Program (MAAP) is an initiative of Amazon Conservation to help stop deforestation in the Amazon. We use satellite technology to monitor deforestation across the entire Amazon as it happens (what we call “real-time”), and then we provide this important information in an easy-to-understand format to policymakers, civil society, researchers, local organizations, media, and the general public so that collective action can be taken against deforestation. We also help empower local people with the data, tools, and technology they need to be able to fight crimes against the forest, such as illegal logging, mining, and wildlife trafficking.

This program is unique because it uses technology to speed up the process of locating, documenting, and stopping deforestation activities. Before MAAP launched in 2015, it could take months or years before local authorities discovered illegal deforestation in the Amazon because the rainforest is so remote, dense, and difficult to navigate. Local authorities would have to take long boat rides or patrol on foot for days to look for and document where deforestation was happening. The people doing the illegal activities would often move on to their next site within weeks or months, much faster than authorities could organize a team to stop them. This changed with advances in technology and MAAP. Now, we can use satellite images to pinpoint where the deforestation is taking place within a matter of hours or days, and then inform the local authorities of the exact coordinates for where to find the perpetrators and stop the illegal deforestation quickly. So now, instead of letting deforestation go on unnoticed and spread quickly for months or years before it can be stopped, we are able to give local authorities the tools to stop them quickly without spending as much time and as many resources navigating the remote forest.

Visit our MAAP website to learn more.

What can I/my classroom/my school do to help protect the Amazon Rainforest?

What can I/my classroom/my school do to help protect the Amazon Rainforest?

You’re already helping us by sharing a little bit about the Amazon Rainforest with your friends, families, and classmates/students! Sharing this information helps educate people about why the rainforest is so important and how – even though it seems really far away from us – it is very interconnected with our daily lives.

If you want to go above and beyond to make a difference in the lives of the wildlife and people living in the Amazon, you can create a fundraising campaign for Amazon Conservation, such as organizing a bake sale or lemonade stand, or consider asking for donations from your family and friends for your birthday or special celebration. All donations enable us to make conservation happen across the Amazon and without them, we would not be able to protect the rainforest. Every penny helps, but most importantly, be creative and have fun!

Another way to support our work is to share our content on social media, which helps amplify the voices of the Amazonian people we represent and spreads awareness of the importance of Amazon (we are on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter/X, and LinkedIn).

Learn more about what you can do for the Amazon here.

What are some resources to learn more about the Amazon Conservation Association?

You can learn more about Amazon Conservation and our conservation efforts by signing up for our newsletter, reading our monthly blog posts, or following our social media pages (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter/X, and LinkedIn). You can also read more about the current state of the Amazon through our MAAP website.

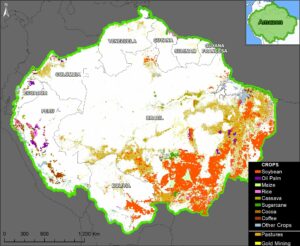

Agriculture has become one of the leading causes of deforestation across the Amazon. As MAAP has continued to closely monitor its impacts, a burst of new data and online visualization tools are revealing key land use patterns across the Amazon, particularly regarding the critical topic of agriculture. MAAP #214, merges and analyzes these new datasets to provide our first overall estimate of Amazonian land use, the most detailed effort to date across all nine countries of the biome that zooms in on three key regions to show the data in greater detail:

Agriculture has become one of the leading causes of deforestation across the Amazon. As MAAP has continued to closely monitor its impacts, a burst of new data and online visualization tools are revealing key land use patterns across the Amazon, particularly regarding the critical topic of agriculture. MAAP #214, merges and analyzes these new datasets to provide our first overall estimate of Amazonian land use, the most detailed effort to date across all nine countries of the biome that zooms in on three key regions to show the data in greater detail:

More than just a natural water resource for local people, the ecosystem’s significance extends far beyond the local community and wildlife. For approximately 2,800 years, the landscape’s seasonal flooding pattern has shaped both its landscape and biodiversity and influenced many socioeconomic and cultural activities. The Mamoré River flows south to north to join the Beni and Iténez rivers and form the Madeira River, one of the main tributaries of the Amazon River. As part of the Llanos de Moxos ecoregion with high levels of flooding and water retention, San Ramón’s lower elevation flood plain helps regulate water levels and flooding for the Amazon, so conservation of the region helps sustain the ecological health of the larger Amazon. In addition, these plains have a strong historical and cultural legacy as they were once home to pre-Columbian societies with complex structural adaptations such as dams, embankments, and ridges that left a valuable archaeological heritage in Beni.

More than just a natural water resource for local people, the ecosystem’s significance extends far beyond the local community and wildlife. For approximately 2,800 years, the landscape’s seasonal flooding pattern has shaped both its landscape and biodiversity and influenced many socioeconomic and cultural activities. The Mamoré River flows south to north to join the Beni and Iténez rivers and form the Madeira River, one of the main tributaries of the Amazon River. As part of the Llanos de Moxos ecoregion with high levels of flooding and water retention, San Ramón’s lower elevation flood plain helps regulate water levels and flooding for the Amazon, so conservation of the region helps sustain the ecological health of the larger Amazon. In addition, these plains have a strong historical and cultural legacy as they were once home to pre-Columbian societies with complex structural adaptations such as dams, embankments, and ridges that left a valuable archaeological heritage in Beni.  With summer in full swing and summer vacation plans looming, we were excited to speak with Eleanor and Malcolm whose passion for birding, as well as socially and environmentally responsible travel, has taken them to many incredible destinations. Concurrently, their travels to some of the world’s most biodiverse regions have also exposed them to some of the biggest risks to the planet, including illegal mining and logging. Through their travels and birding, Eleanor and Malcolm have become increasingly committed to helping protect the Amazon and doing what they can in the face of climate change.

With summer in full swing and summer vacation plans looming, we were excited to speak with Eleanor and Malcolm whose passion for birding, as well as socially and environmentally responsible travel, has taken them to many incredible destinations. Concurrently, their travels to some of the world’s most biodiverse regions have also exposed them to some of the biggest risks to the planet, including illegal mining and logging. Through their travels and birding, Eleanor and Malcolm have become increasingly committed to helping protect the Amazon and doing what they can in the face of climate change.

In previous MAAP reports, such as

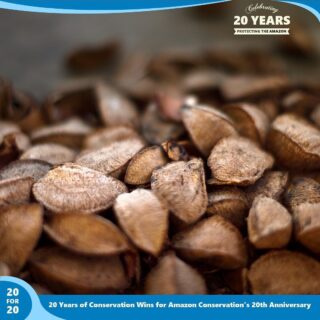

In previous MAAP reports, such as  The Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) is a key product of wild collection in the Amazon forests and serves as a crucial source of income for families in the Madre de Dios region of Peru. For years, our alliance with our sister organizations Conservación Amazónica – ACCA and Conservación Amazónica – ACEAA has helped Brazil nut, açaí, and other forest product harvesters earn organic certifications to follow forest-friendly guidelines that keep production sustainable and mitigate harm to Amazonian forests.

The Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) is a key product of wild collection in the Amazon forests and serves as a crucial source of income for families in the Madre de Dios region of Peru. For years, our alliance with our sister organizations Conservación Amazónica – ACCA and Conservación Amazónica – ACEAA has helped Brazil nut, açaí, and other forest product harvesters earn organic certifications to follow forest-friendly guidelines that keep production sustainable and mitigate harm to Amazonian forests.

How does deforestation impact wildlife/fauna and flora?

How does deforestation impact wildlife/fauna and flora? How many species are there in the Amazon? What are some of the most endangered species in the Amazon?

How many species are there in the Amazon? What are some of the most endangered species in the Amazon?  How does climate change impact the Amazon, its people, fauna, and flora?

How does climate change impact the Amazon, its people, fauna, and flora? What is Amazon Conservation doing to protect the Amazon Rainforest?

What is Amazon Conservation doing to protect the Amazon Rainforest? What is the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Program (MAAP) and how does it help combat deforestation?

What is the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Program (MAAP) and how does it help combat deforestation?  What can I/my classroom/my school do to help protect the Amazon Rainforest?

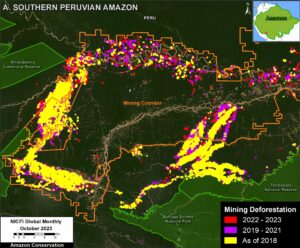

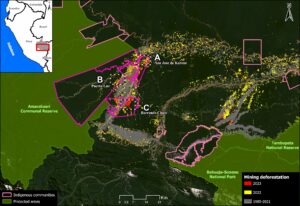

What can I/my classroom/my school do to help protect the Amazon Rainforest?  Gold Mining is one of the major deforestation drivers across the Amazon, often targeting remote areas such as protected areas and indigenous territories. Given the vastness of the Amazon, accurately monitoring mining deforestation in the most real-time, up-to-date format has been a challenge.

Gold Mining is one of the major deforestation drivers across the Amazon, often targeting remote areas such as protected areas and indigenous territories. Given the vastness of the Amazon, accurately monitoring mining deforestation in the most real-time, up-to-date format has been a challenge. In addition to our incredibly dedicated staff members, our Board of Directors is made up of passionate science, business, and civic leaders who provide their expertise and financial support to help guide our mission in the most strategic direction. With their commitment to protecting the Amazon Rainforest, we can help take action on the ground for both people and wildlife.

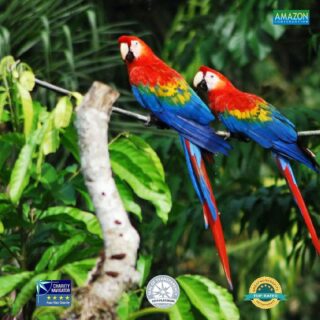

In addition to our incredibly dedicated staff members, our Board of Directors is made up of passionate science, business, and civic leaders who provide their expertise and financial support to help guide our mission in the most strategic direction. With their commitment to protecting the Amazon Rainforest, we can help take action on the ground for both people and wildlife. For Board Chair Jim Brumm, who joined Amazon Conservation’s Board of Directors in 2016, the great outdoors has always been a place of solace, especially for bird watching. He has traveled near and far to marvel at the vast array of bird species across the globe and was lucky enough to find the opportunity to become a Board Member through this passion. Jim is also deeply interested in and committed to conservation, Indigenous peoples, and community rights and development, and has served and continues to serve on a number of boards involved in bird conservation, Indigenous peoples’ rights, animal welfare, and conservation science.

For Board Chair Jim Brumm, who joined Amazon Conservation’s Board of Directors in 2016, the great outdoors has always been a place of solace, especially for bird watching. He has traveled near and far to marvel at the vast array of bird species across the globe and was lucky enough to find the opportunity to become a Board Member through this passion. Jim is also deeply interested in and committed to conservation, Indigenous peoples, and community rights and development, and has served and continues to serve on a number of boards involved in bird conservation, Indigenous peoples’ rights, animal welfare, and conservation science. What got you interested in environmental conservation?

What got you interested in environmental conservation? As a Board Member, what are you most impressed/proud of from Amazon Conservation?

As a Board Member, what are you most impressed/proud of from Amazon Conservation? Our newest MAAP report,

Our newest MAAP report,  Loading...

Loading...