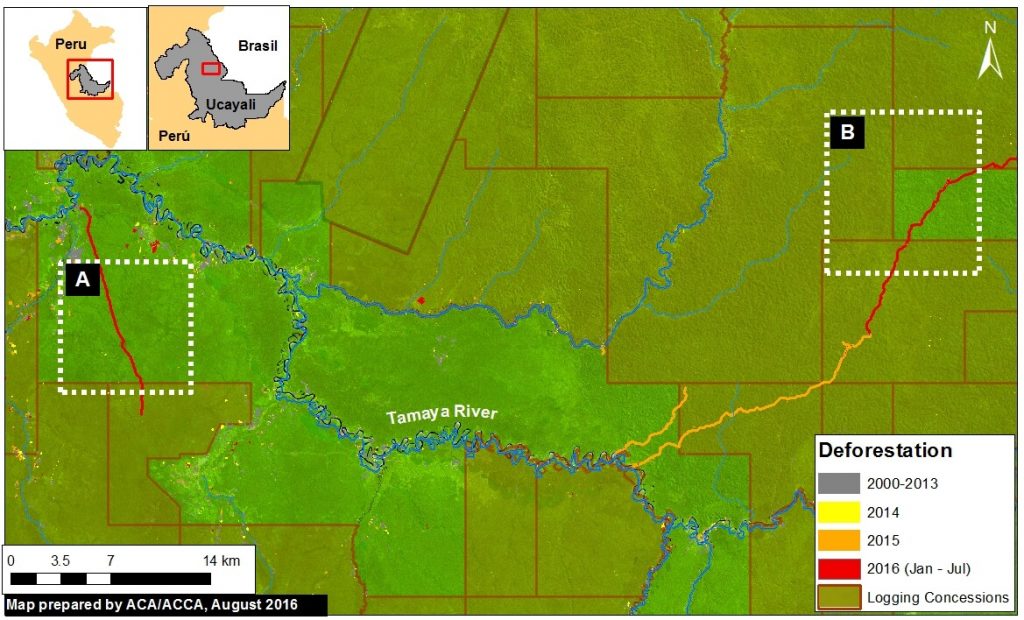

In the previous MAAP #4, we documented the deforestation of 6,464 hectares (15,970 acres) between 2011 and 2015 associated with a large-scale oil palm project in the central Peruvian Amazon (Ucayali region) operated by the company Plantaciones de Pucallpa. In addition, we found that the majority of this deforestation occurred in primary forests,1 although there was also clearing of secondary vegetation.

In December 2015, the Native Community of Santa Clara de Uchunya presented an official complaint to the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) against Plantaciones de Pucallpa, a member of the roundtable. An important component of the complaint centers on the deforestation described above, however the company has repeatedly denied causing it.

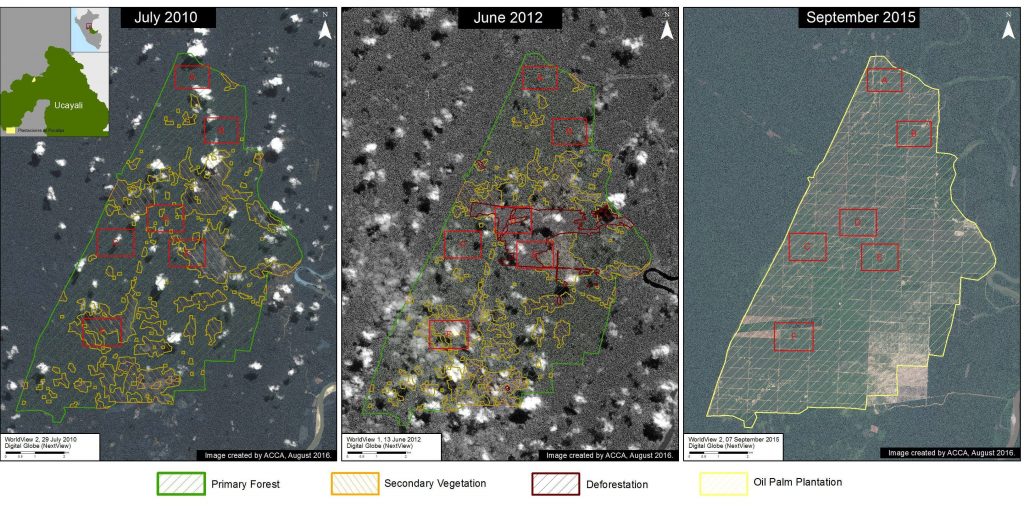

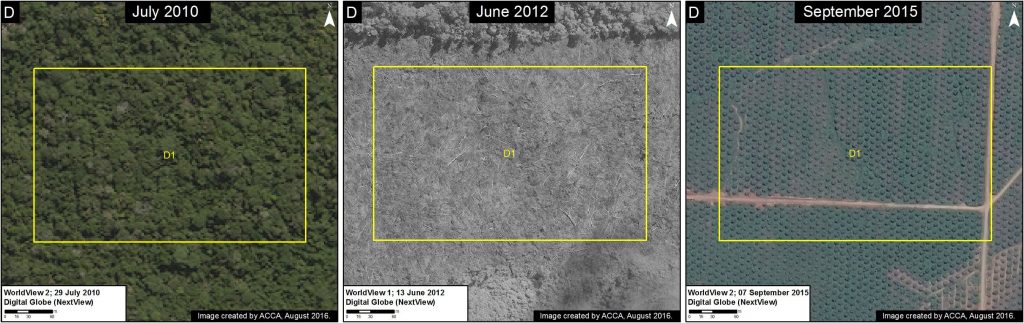

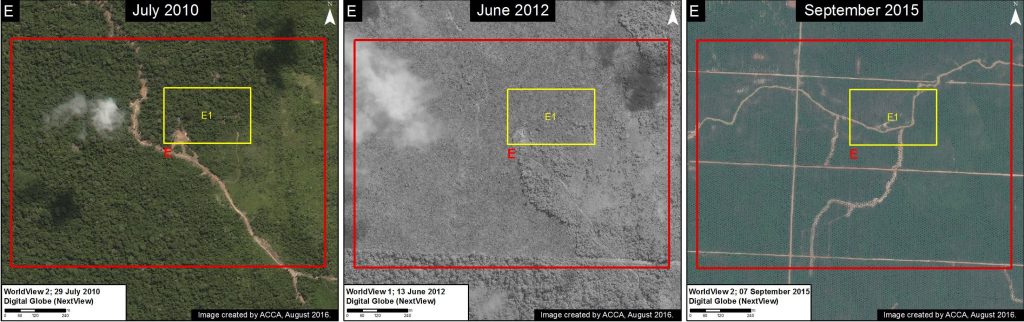

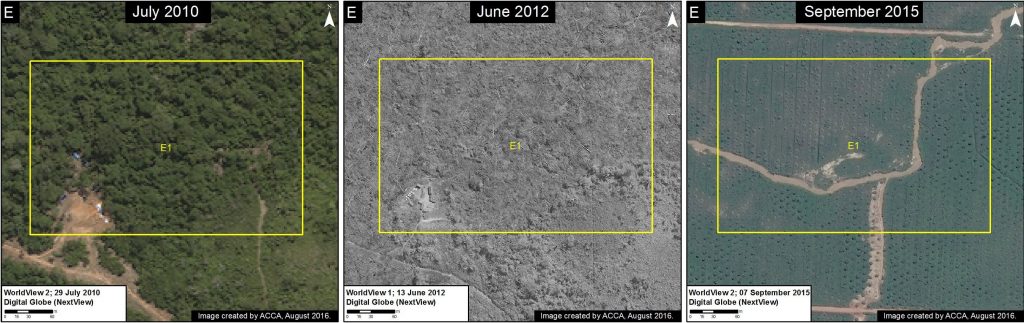

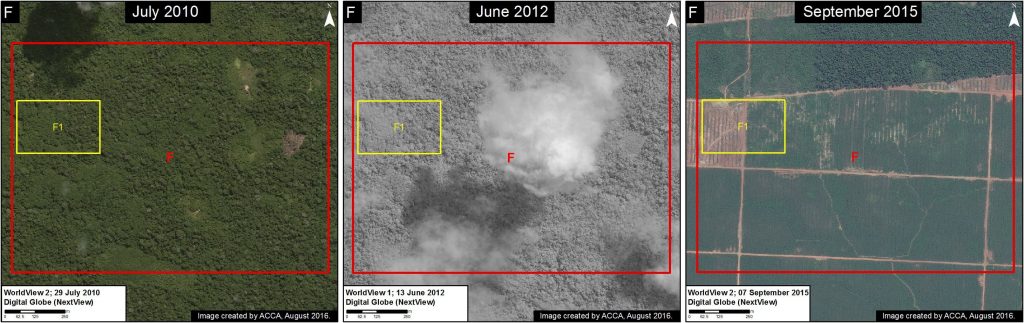

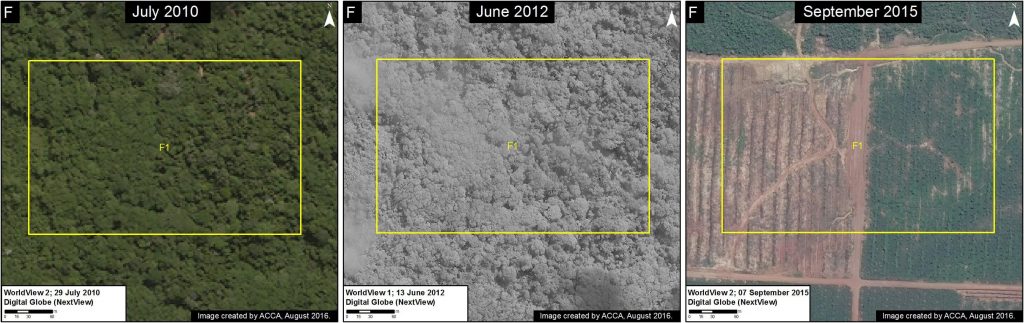

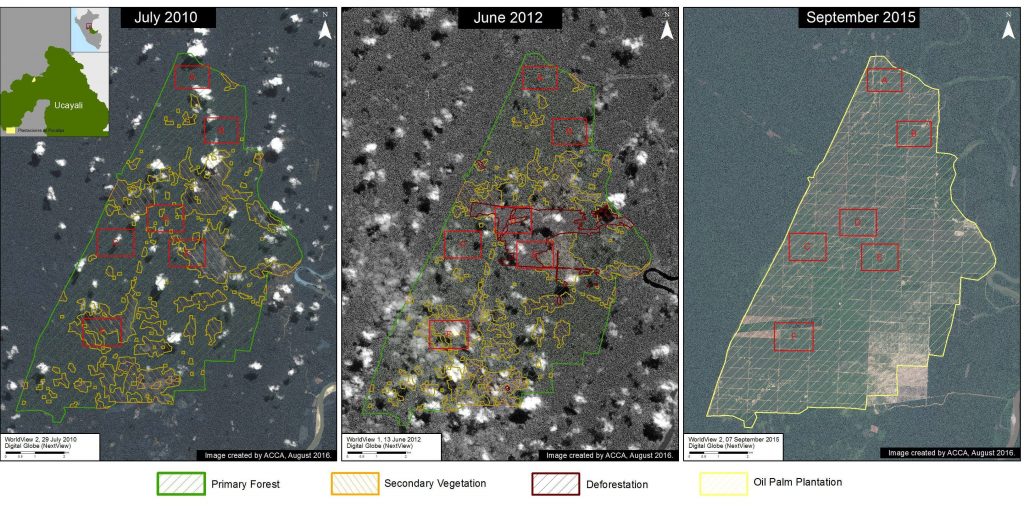

To better understand the deforestation in question, we compare three high-resolution satellite images: 1) July 2010, the most recent high-resolution, color image prior to the start of large-scale deforestation in May 2012; 2) June 2012, a black and white image from the time period when large-scale deforestation began; 3) September 2015, color image showing the established oil palm plantation.

Image 41a shows a base map of the project area in July 2010 (left panel), June 2012 (center panel), and September 2015 (right panel). We indicate areas of primary forest and secondary vegetation,2 recently deforested areas, and oil palm plantation. The images show that large-scale deforestation had begun by June 2012, and by 2015 there was a complete transformation of primary forest and secondary vegetation to large-scale oil palm plantation. Insets A-F show the areas detailed in the zooms below. Click on images to enlarge.

Image 41a. Data: Digital Globe (Nextview), MAAP

[separator]

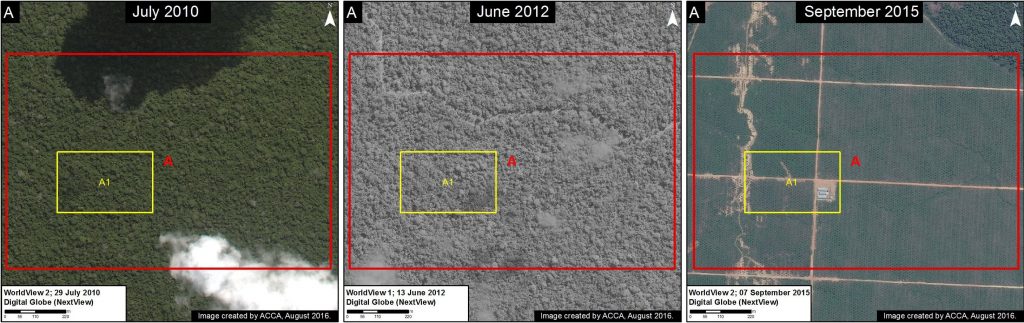

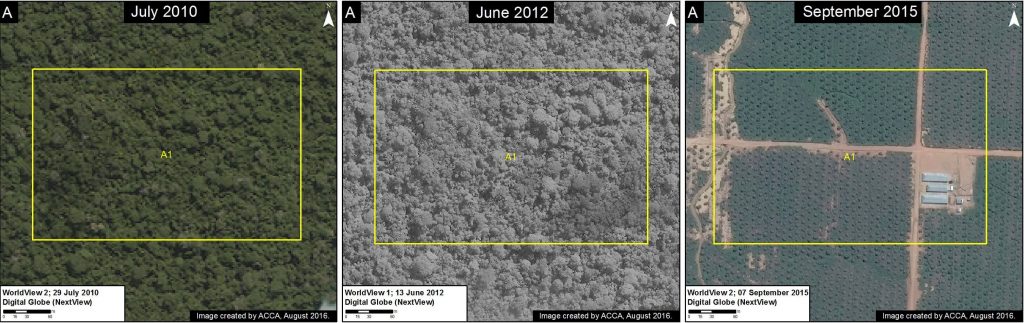

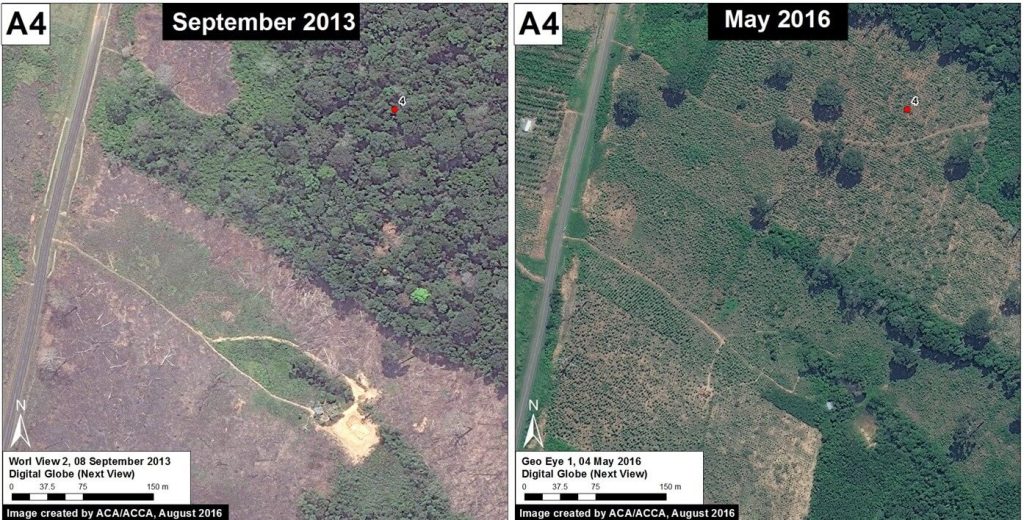

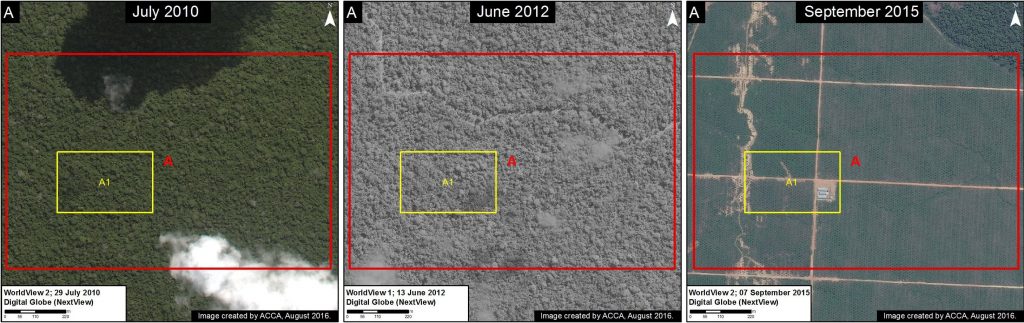

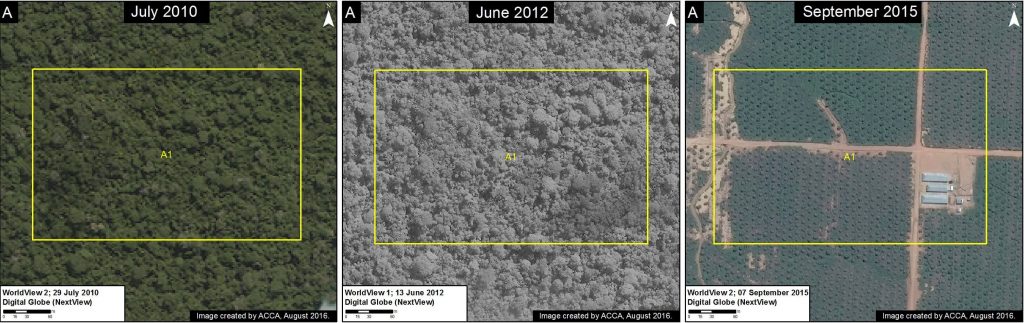

Zoom A: Primary Forest

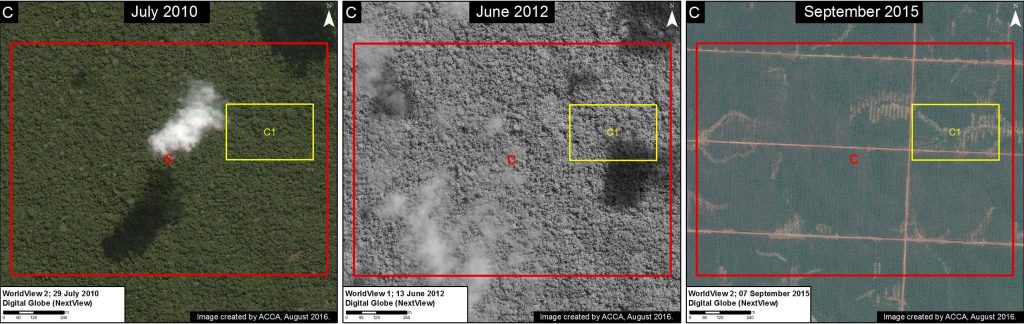

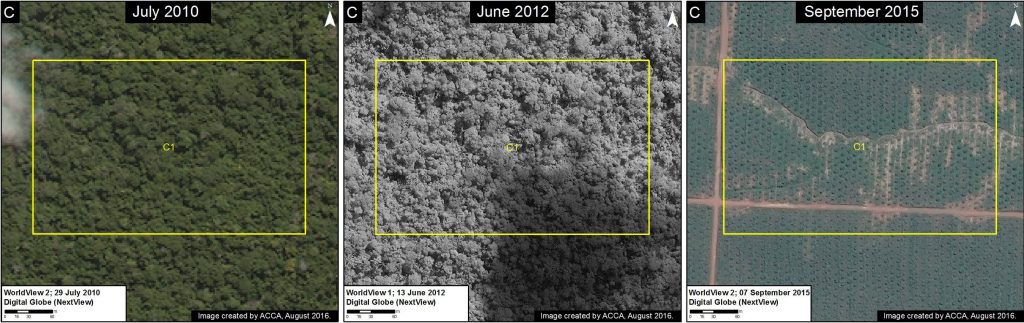

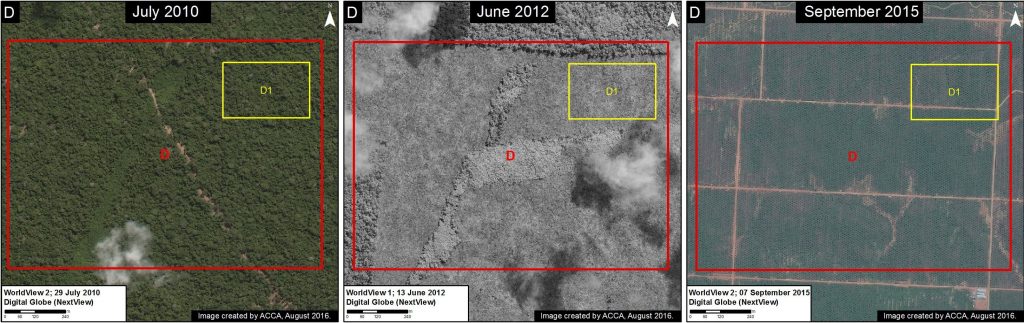

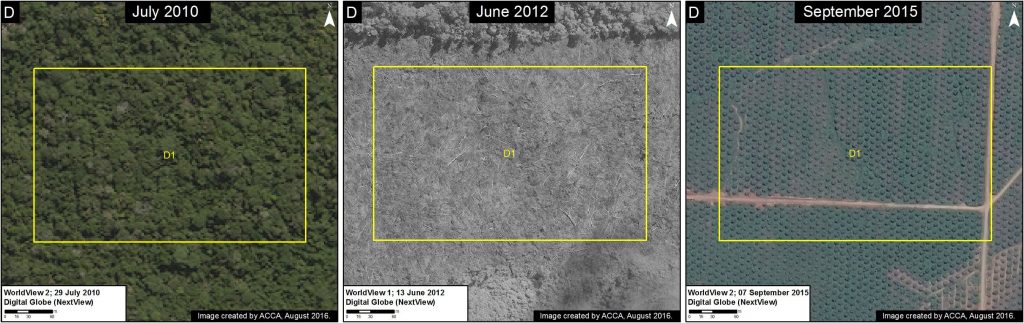

Images 41b-i show the zooms of the areas (Insets A – D) in which installation of the oil palm plantation replaced primary forest. The images show primary forest in July 2010 (left panel) and June 2012 (center panel) replaced by oil palm plantation in September 2015 (right panel). Note that in Inset D (Images 41h-i), recently cleared trees can seen as the large-scale deforestation was just starting at that time3.

Image 41b. Data: Digital Globe (Nextview)

Image 41c. Data: Digital Globe (Nextview)

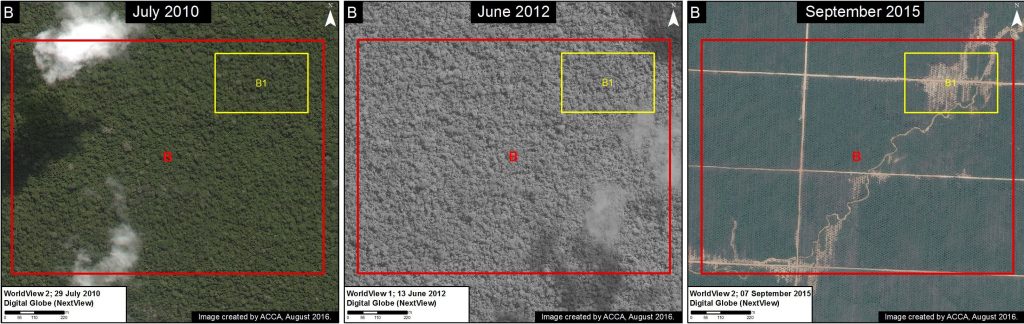

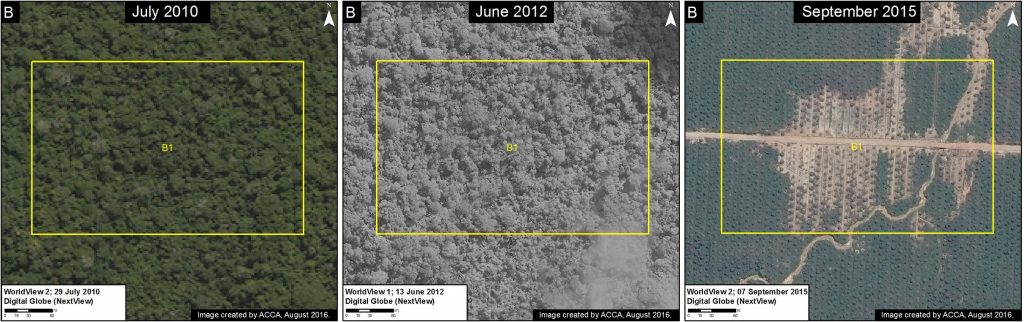

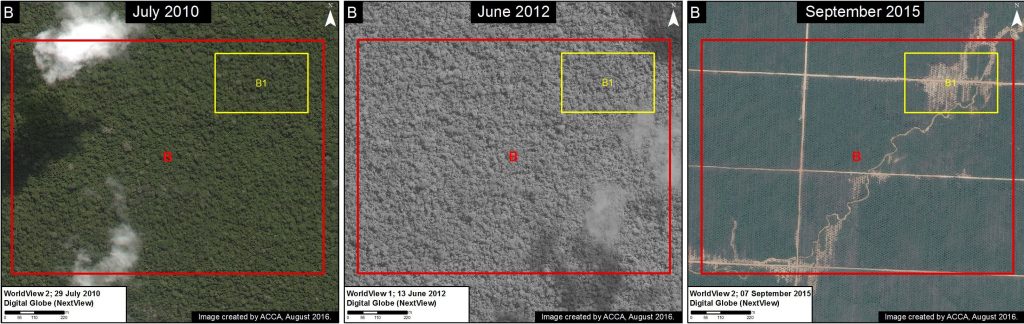

Zoom B: Primary Forest

Image 41d. Data: Digital Globe (Nextview)

Image 41e. Data: Digital Globe (Nextview)

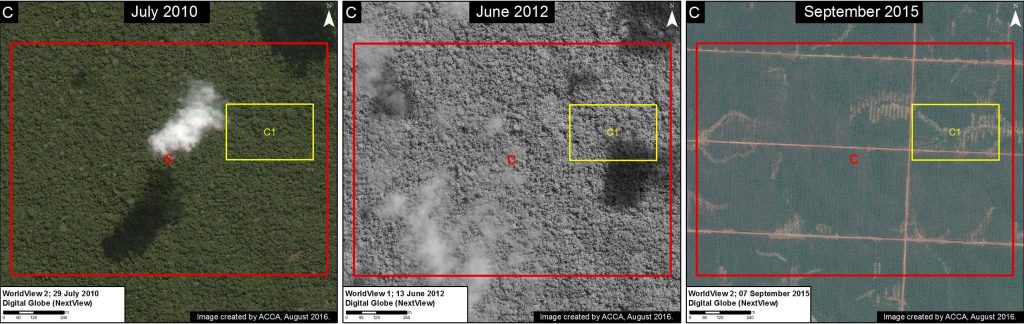

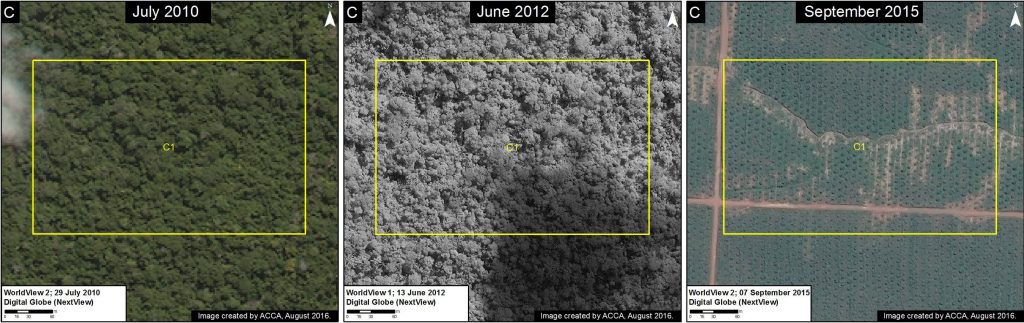

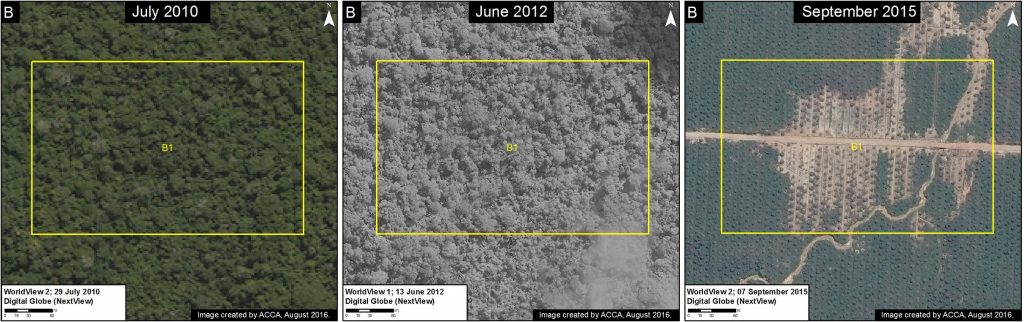

Zoom C: Primary Forest

Image 41f. Data: Digital Globe (Nextview)

Image 41g. Data: Digital Globe (Nextview)

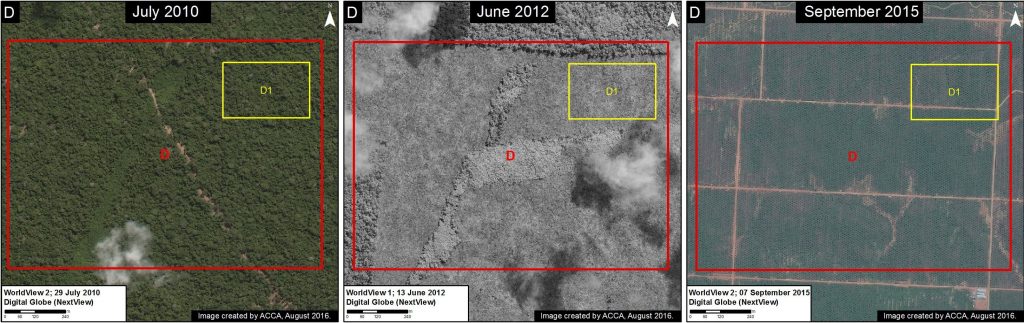

Zoom D: Primary Forest

Image 41h. Data: Digital Globe (Nextview)

Image 41i. Data: Digital Globe (Nextview)

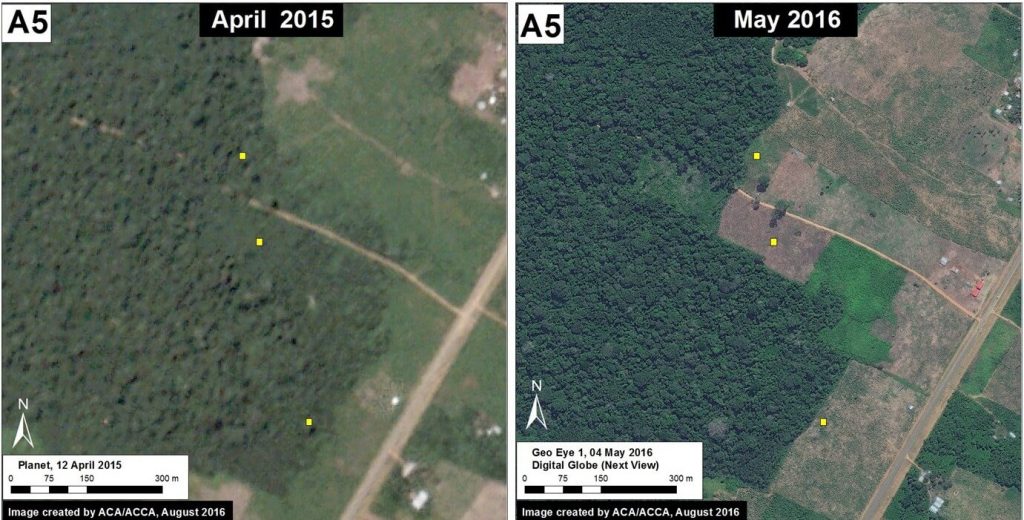

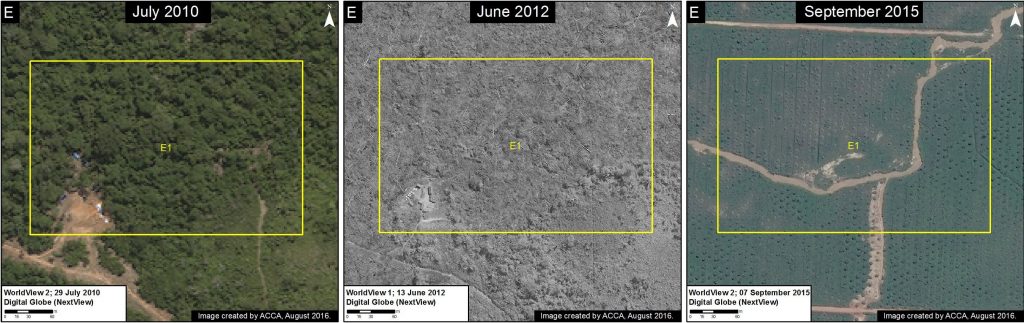

Zoom E: Secondary Vegetation

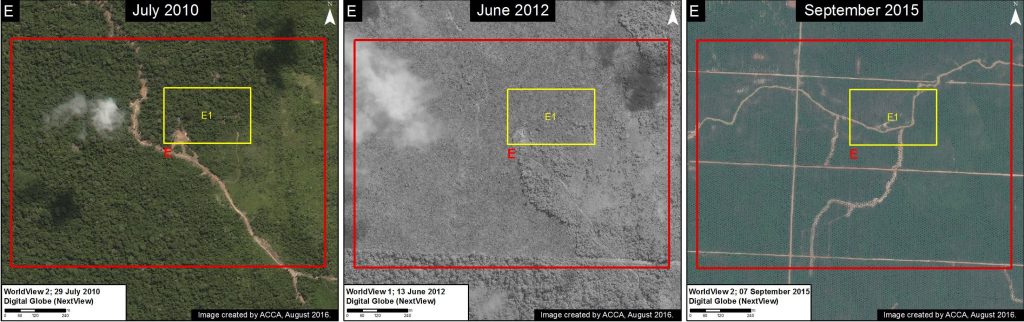

Images 41j-m show the zooms of the areas (Insets E – F) in which the oil palm plantation replaced secondary vegetation. The images show secondary vegetation in July 2010 (left panel) and June 2012 (center panel) replaced by oil palm plantation in September 2015 (right panel).

Image 41j. Data: Digital Globe (Nextview)

Image 41k. Data: Digital Globe (Nextview)

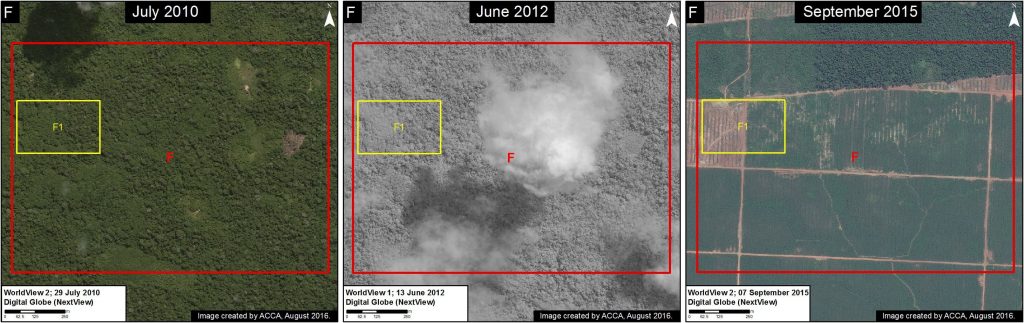

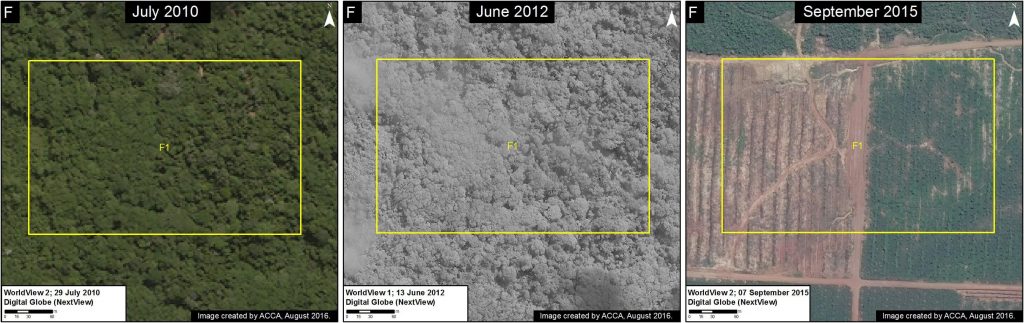

Zoom F: Secondary Vegetation

Image 41l. Data: Digital Globe (Nextview)

Image 41m. Data: Digital Globe (Nextview)

Notes

1 We define primary forest as an area that, from the first available Landsat image (in this case 1990), was characterized by a forest cover of closed and dense canopy. This definition is consistent with the official definition of the new Forest Law: “Forest with original vegetation characterized by the abundance of mature trees with superior or dominant species canopy, which has evolved naturally.”

2 Primary and secondary forest classifications come from the analysis published in MAAP #4

3 Analysis of additional satellite imagery reveals that the large-scale clearing started between May and June 2012.

Citation

Finer M, Cruz C, Novoa S (2016) Confirming Deforestation for Oil Palm by the company Plantations of Pucallpa. MAAP: 41

Loading...

Loading...